Serenade in G major, K. 525 “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

by WOLGANG AMADEUS MOZART

1787 was a most eventful year for Mozart. Don Giovanni was commissioned, composed and produced. In April and May of that year Mozart composed the two pinnacles of his chamber music output, the String Quintets in C major and G minor. Additionally, a young Beethoven visited him in his Blutgasse Apartment behind St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna with Mozart promising to teach him. In May of 1787, his father Leopold died. Eine kleine Nachtmusik was composed during a respite from the composition of Act II of the da Ponte opera. In October, Don Giovanni was produced; in December he was appointed court composer by Emperor Joseph II; and his daughter Theresia was born. Perhaps our overextended lives aren’t anything new?

Eine kleine Nachtmusik is dated August 10, 1787 and one thing is sadly certain—there is a lost movement. All serenades contained two minuet movements. We are left with the tantalizing entry of the lost movement in Mozart’s own catalogue listing. The missing movement would follow movement one. That the orchestration is only for strings is also unique for this entertainment genre. But all this now hardly matters. Eine kleine Nacthmusik is a musical equivalent of a famous line of Shakespeare, reminding us from time to time that clichés become clichés for a very, very good reason. This is Don Giovanni without its complicated drama, just pure and simple love music, especially in the famous Romanze. This favorite G major serenade is deserving of its audience affection, a wonderful combination of integrity and accessibility.

— Jeff von der Schmidt

Baalkah

by GABRIELA ORTZ

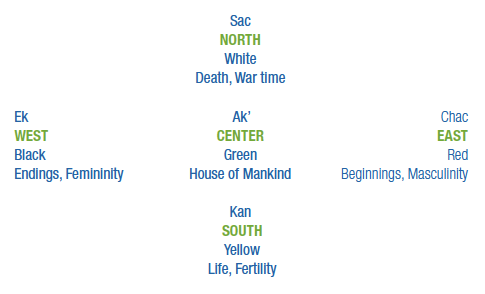

Baalkah, which means “world” or “cosmos” in Maya, was inspired by the cosmological beliefs of the Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula and of other Mexican and Central American Native peoples. For over 5,000 years, these Indian peoples have conceived of the world as being divided into four cardinal directions: East, North, West and South. In each one of these directions stands a gigantic Ceiba tree that supports the sky, and each one has its particular cosmological characteristics, such as its own ruling deity, its own color, a set of related plants and animals, and more generally, its own mood or personality.

This quadripartite division of the world is closely related to time: each year is associated to a specific cardinal direction, and thus time rotates around the world every four years, from East to North to West to South, bringing with itself the influences pertaining to each direction. These forces are both positive and negative, since in Indian thought there is no pure good and no pure evil. In the Center of the World, where mankind lives, all the characteristics of the four directions mingle.

The task of humankind is to assimilate and channel the influences that flow from each direction to ensure harmony and stability in the center. At the beginning of each year, the Mayas arrange a four legged table, symbolizing the Cosmos, with offerings to the deities of each of the four directions, thus guaranteeing that their world will remain firmly anchored and in harmony.

The lyrics of the first four songs of Baalkah are taken from a 17th century Maya book, the Chilam Balam of Chumayel, a priceless depository of centuries of historical and religious wisdom inherited by Maya priests and kept hidden from the prosecution of the Catholic Church. Each member of the string quartet represents one of the four cardinal directions, and the center is represented by the soprano.

The songs, in turn, express the moods and characteristics of their corresponding cardinal point. Chac and Ek, related to dawn and masculinity, and to dusk and femininity, respectively, are static and serene. Sac and Kan, related to death and war, and to fertility and life, are dramatic and powerful. Finally Ak’, the center, gives pride of place to the voice of the soprano, representing humankind, in an expressive, melismatic chant.

— Federico Navarrete

NEW RELEASE: Music by Gabriela Ortiz

recorded by Southwest Chamber Music

purchase your copy this evening!

Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)

by ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

“Yesterday evening I heard Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4, and I would consider it a sin of omission if I did not say a word of thanks to you for your wonderful sextet. I had intended to follow the motives of my text in your composition, but I soon forgot to do so, I was so enraptured by the music.” This letter of December 12, 1912 from Richard Dehmel to Arnold Schoenberg attests to the ability of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) to transform the listener. It was Dehmel’s poem by the same name from an anthology entitled Weib und Welt (Woman and World) that inspired Schoenberg’s music. In an article called “My Evolution,” written while the composer lived in Los Angeles, Schoenberg made no attempts to disguise the music’s debt to both Brahms and Wagner. His predilection for juxtaposition of ideas and unity of form is clear in Verklärte Nacht, concerns which intensified with the succeeding works Pelleas und Melisande, Op. 5, the String Quartet No.1 in D minor, Op. 7, and the Kammersymphonie, Op. 9. A year before his death in 1950 Schoenberg wrote about this work: “My composition was, perhaps, somewhat different from other illustrative compositions, firstly, by not being for orchestra but for a chamber group and secondly, because it does not illustrate any action or drama, but was restricted to portray nature and to express human feelings.”

Those feelings, as represented by Dehmel’s poem, remain current and topical. The narrative describes the predicament of a woman who is pregnant from what we would today call an abusive relationship. She has subsequently fallen in love with a man who is not the father of the child. Schoenberg’s composition tells the story of the evening walk where she has finally summoned up the courage to tell the new man in her life the truth about her past relationship and her current pregnancy. The woman’s intense fears of what this revelation will bring prove to be unfounded. She has indeed found the “right” man, who tenderly tells her that he understands her past situation, that he will not withdraw his love because of the current circumstance, and that they will raise the child as their own. As these now assured lovers continue their walk, the night is transfigured before them in one of music’s most magical conclusions, resolving the visible darkness of the psychological fear of devastating rejection with the tranquility of returned love and affection, a blissful All’s Well That Ends Well to this fateful walk in the woods.

— Jeff von der Schmidt